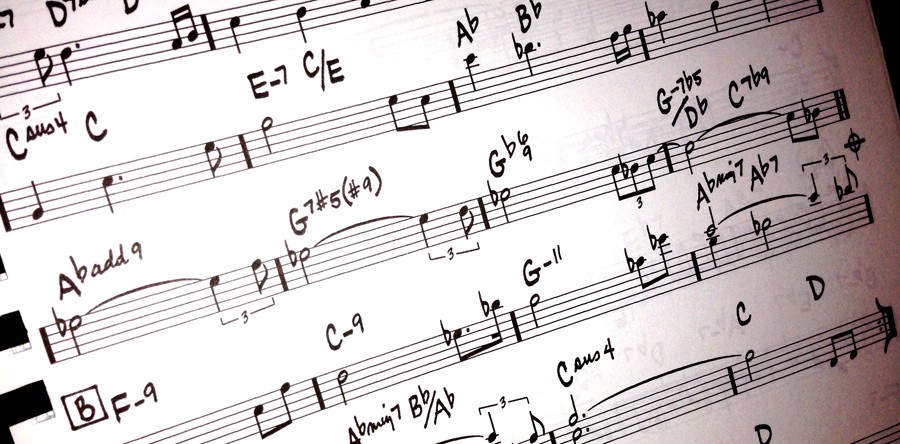

The Trouble with Chord Symbols

There often seems to be confusion and disagreement about chord symbols (not just among students, but professional musicians as well!) This is something I’ve thought about a lot and covered extensively in my “Chord Construction Workshop” series (you can access those lessons by becoming a member on this site for free). Truth be told, since chord symbols are really simply a kind of short-hand notation, good rhythm section players use their ears and taste just as much as what’s written on the page to give the best rendering of the writer’s intention. So it’s just as much art as it is science. With this in mind, here are some thoughts about best practices in chord symbol notation.

The Basics

Many ago I learned at Berklee

- NO SUFFIX for a Major triad

- “min” “mi” or “m” for minor triad

- “Maj7” (not the Delta sign for Major 7)

- “min7” “mi7” or “m7” (never the “-7” sign)

- “min7(b5)” and not the half-diminishished symbol (the circle with the slash through it)

- “o7” for diminished 7th was fine though, so go figure.

Chord Extensions and Alterations

Here are some other helpful “rules” to remember when writing, reading and interpreting chord symbols:

- 9, 11 or 13 indicated after the root with nothing preceding them are all dominant7 family chords and built from a Mixolydian chord/scale. It’s really simple if you just think of the Dominant 7th or “Mixolydian” Scale being the default state of affairs when dealing with chord symbols. Everything else is always indicated.

- To keep things clear, alterations must come after the the initial suffix. For instance C#9 means something very different than C7#9. Similarly C#11 is in no way the same chord as C9#11. It also often helps to put the alterations in parethesis as in C7(#9), C9(#11), etc. but this convention is not always held to. As long as the symbols are in the correct order, that’s usually enough.

- min7 (or the minus sign) lowers the 3rd (the 7th is already lowered by default). This also applies to min9, min11 and min13.

- Maj7 (or the delta sign) simply raises the 7th making it Major since the 3rd is already major (unless “min” is in the symbol first, as in Cmin(Maj7) ). These rules apply also to CMaj9, CMaj13, and Cmin9(Maj7). Since “natural 11” is considred an avoid, we’ll deal with Well deal with “11” separately in the alterations below

Also note that when actually “voicing” these chords, extension notes are generally not “added” but rather substitute for an existing note in the upper voicing so:

- sus4 replaces 3 and can be added to triads or Dominant 7th chords. It’s sometimes seen on min7 chords, generally indicating a Quartal voicing (think “McCoy Tyner)

- 5 can be raised or lowered (as in “b5 or #5) on Maj7, Min7 or Dominant 7th chords.

- 9 replaces 1 (can be also be raised as in “#9” or lowered as in “b9”).

- 13 replaces 5 (13 can be also lowered as in “b13”)

- #11 replaces 3 (#11 usually replaces the 5, but if 13 is present, then often replaces 3)

Shortening Chord Symbols

In the real world and on the bandstand keeping the chord symbols clear and compact has great advantages. Just start writing a passage where there’s a different chord every beat and any thought of doing things like writing “maj7” go out the window. And min7(b5) (because the alteration is really supposed to be in parenthesis) forget about it! Who can afford to spare that much real estate? So, going against my old Berklee training, I’m a big fan of using the delta sign for maj7, -7 for m7 (because they’re compact, don’t resemble anything else, and therefore don’t clutter the page or cause visual confusion), o7 for dim7, and the half-diminished symbol (small circle with a slash through it) for min7(b5).

Understanding the Composer’s Intention

In reading a jazz chart where the chords are being simply notated like; D- G7 C A-, it’s probably going to be obvious to the player that extensions and embellishment is expected. These are usually arrived at spontaneously through listening to the melody or soloist and responding accordingly. In other styles of music (rock, country, etc.) you’re probably going to be expected to just “play what’s on the page” so a good knowledge of styles is prerequisite. You obviously need to listen to a lot of whatever style of music you’re going to be playing and learn what’s expected and appropriate.

In most music a traid requires no suffix, but as noted before jazz musicians are so used to adding extensions to major chords, that if the arranger REALLY wants nothing but a triad, they might write “C Triad” (seems a bit excessive, but it gets the point across). Then again, if they’ve been very specific with all their suffixes consistently, and the write “C,” I think it’s pretty clear that they probably just want a triad. So the art part of this (that was mentioned before) is learning to interpret an individual arrangers style and intention. The more of thier music you play, the easier this becomes.

Some Useful Jazz Resources

The absolute best and most definitive guide I’ve ever seen on this subject was in the back of Clinton Roemer’s long out of print classic “The Art of Music Copying.” It’s sometimes possible to find a used copy of this on the internet. It’s worth looking for and I highly recommend it! Although the opening sections about penmanship and supplies are now somewhat dated (since almost everybody’s using notation software nowadays), the guidelines for laying out parts, how to mark sections, page-turns, and a slew of other practical topics, are timeless (and a lot of the gripes that musicians had about computer generated notation in the beginning was really that the computer operator simply didn’t understand the basics of good part layout, and though things have improved a bit, you still can’t expect the computer to do these things for you correctly! Always check and tweek!)

World reknowned jazz educator Jamey Aebersold‘s website www.jazzbooks.com is a fantastic resource. You can find books and play-a-longs on almost anything jazz related. Also pertinent to this topic are some free booklets and articles you can download from his site. Follow the dropdown menu for “Free Jazz” and get a copy of his Jazz Handbook, Scale Syllabus and Jazz Nomenclature.

Sher Music Co. publishes many great jazz books, including the “New Real Book” series and pianist Mark Levine’s very excellent “Jazz theory Book.” Have questions about almost anything in jazz terminology? the answer’s probably in there! Visit www.shermusic.com.

A Slight Rant

One really maddening thing I’ve seen in charts in recent years was that in the “Jazz Font” used in Finale, they use a small-cap for lower case M, so all of the m7, m9 chords etc. Look like M7, M9 (whichon first glance, you’re going to interpret as major). Really causes LOTS of train-wrecks in rehearsals!

A Proposed Solution

Personally, I think a lot of the problem is that our keyboard and character set just don’t allow for some of the simple, short characters. It really wouldn’t be that difficult to create a font that contained everything you needed (without having to change fonts constantly when entering suffixes like we have to do in Finale and Sibelius). The Delta symbol could be mapped to the “^” key (do you ever have to type the carat symbole when entering chords?) the half-diminished symbol could map to “h” or “0” (that’s the zero in case it’s not obvious in this font, and again neither of those are ever really used in chord notation), the flat symbol should obvious map to lower case “b” (since you always type roots as capital letters), the the sharp to “#” and we’d be all set. (can anybody think of anything I missed?)

In Closing

If you’ve enjoyed this post, and if you do, please take a second “Like” my page and share it (facebook, twitter, tumblr, etc.) and of course, feel free to leave your comments below. I love hearing from my readers and our conversations help me to know what you’d like to see here!

Thanks!

Musically Yours,

~ Rick Stone

If you’d like to here some of my music, please visit http://www.rickstone.com