Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

David,

Emily Remler, Sheryl Bailey and a lot of the Berklee schooled players (and that included me) were into that 2 and 4 thing. It “kind of works” up to a point, but I learned later on that it was actually holding me back.

When I studied with Hal Galper about 25 years ago, he made this really clear. Now all this information is out there in the form of Youtube videos. Check this one out first (I think it will answer a lot of questions).

I’ve got to give a lesson right now, but if you’ve got further questions, I’ll be back on in a couple hours.

-

This reply was modified 9 years, 6 months ago by

Rick Stone.

-

This reply was modified 9 years, 6 months ago by

Rick Stone.

-

This reply was modified 9 years, 6 months ago by

-

David,

Practicing slowly at first is always a good idea. Make sure that you’re crystal clear about what you’re trying to play. That includes knowing; the sound of every note (you know I’m a big fan of singing everything), the name of the note, the physical location on your instrument, and the tactile feel of each note under your fingers as you play it. There are things that you learn from doing this that you just don’t get if you’re rushing through things.

That said, some people assume that you just keep gradually increasing the tempo until you get it to where you want it. And to a certain degree, that approach works, but it’s not always an efficient use of practice time. There will always be some parts that you already know pretty well and don’t require that much attention, others that feel near impossible, and progress is slow.

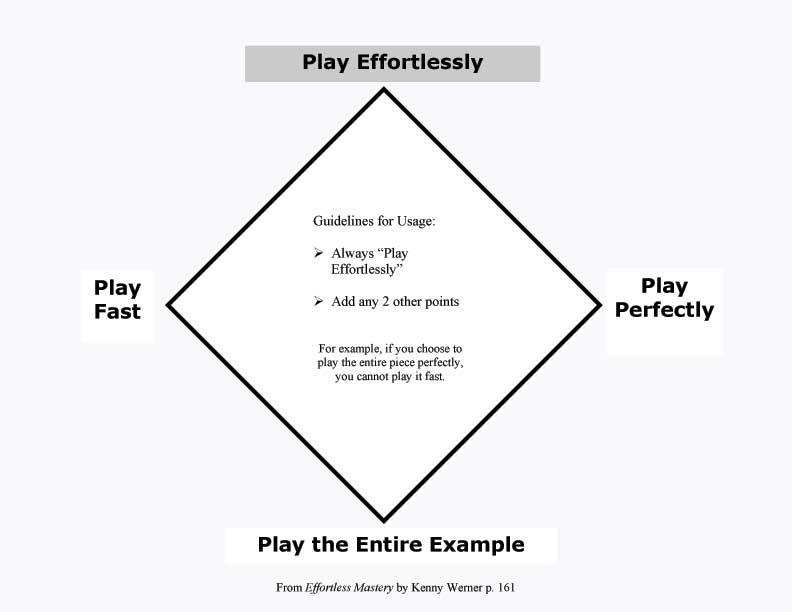

Fortunately, there’s a better way. I stumbled upon this quite accidentally back in the early 1980s and it became my main method of practicing new material. Then, some years later, I was reading Kenny Werner’s book “Effortless Mastery” and he pretty much describes the same procedure which he refers to as “The Learning Diamond”

The idea is that in order to play effortlessly, you need to systematically sacrifice one of the other attributes on the diamond.

So you might:

1) Play the whole thing perfectly, but slowly (sacrifice “fast”)

2) Play short bursts of notes fast and perfect (sacrifice playing the “whole thing”)

3) Play the whole thing fast, but don’t worry about “perfect”I find it very beneficial to cycle through the above three steps repeatedly over a period of time. One of the reasons this works so well is that “playing fast” is not the same as playing slow only faster. There are sometimes logistical issues that don’t become apparent until you try to play something fast (fingerings, picking, etc.). Remember that you’re also developing muscle memory as you do this, so it’s good to be really clear about your fingering and picking, etc.. It’s better to find that out early in the process before you’ve invested a lot of time (and have to unlearn something that turns out not to work so well).

Also, never expect everything to happen on the first day you practice something new. The first day you play a new piece, study or lick, you’ll probably play it slowly a lot. Just take your time and memorize it. Try to sing everything. Some of it might come very easy, but you’ll bump into little glitches. Spend some time trying to work those out and getting them up to temp (sometimes just a measure or two at a time). The first practice session on anything new is usually a long one. But to make it stick, it needs to be repeated on a daily basis for a period of time (usually a few weeks). Luckily the daily time spent on the new piece of material decreases as time goes on, so it opens up time in your practice schedule to learn something else.

So when I’m learning something new, the time spent on a particular piece or exercise might look like this:

Day 1: 40-60 minutes

Day 2: 35-40 minutes

Day 3: 30-35 minutes

Day 4: 25-30 minutes

Day 5: 20-25 minutes

Day 6: 15-20 minutesEtc. Until by the 3red week, I’m probably just running through it once or twice (maybe 3-5 minutes) just so that I don’t forget it (and by then, I’m well familiar with it and it feels quite easy).

I might also mention that what you decide to define as “the whole thing” can be somewhat variable. If you’re learning a long and difficult classical piece, you may decide to break it into a series of mini-goals, and so the “whole thing” may just be a 16-bar section for instance.

As far as metronomes go, I’ll say that I’ve used them (and still do sometimes) but for jazz playing, I infinitely prefer playing with a great drummer; enter this amazing little app I’ve started using recently called DrumGenius. It’s actual 8-bar loops of drummers playing grooves from Billy Higgins, Max Roach, Art Blakey, Jo Jones, etc. Really awesome! It just feels so much better than playing with a dreary “tick tick tick.” The app itself is free but after you download your first three grooves, you’ll have to purchase credits to get additional loops. Trust me, just pay the $12.99 and get the unlimited pack (you’ll wind up saving money in the long run). Totally worth it!

If you’re interested in Kenny’s Book, you can get it directly from Jamey Aebersold.

-

This reply was modified 9 years, 6 months ago by

Rick Stone.

-

This reply was modified 9 years, 6 months ago by

Rick Stone.

-

This reply was modified 9 years, 6 months ago by

Rick Stone.

-

This reply was modified 9 years, 6 months ago by

-

David,

Yes, there’s certainly more than one way to go about it, and after all the forms are learned, playing them across the neck and through the forms EADGC (basically “Hey Joe” backwards) is a great way to practice (and that’s often what I do for a warmup). But until each form is learned and natural, I think playing it up through the keys chromatically using a single form is the way to go. That way your hand, ears and mind get totally familiar with the sound and feel of each one. And as the fingerings start to get easier, you’re still giving your brain a good workout by spelling them properly in each of the keys.

Musically Yours,

~ Rick -

David,

Yes, I intend to do videos (or at least make pdfs) for the four remaining forms. To be honest, when I learned these, I just worked them out on my instrument. After initially memorizing the forms using scale degrees I found practicing them very slowly while saying the note names to be the most helpful. Going slow is really important because it gives you time to think about and absorb the sound and meaning of every note played.Try this:

1) Memorize the entire syllabus using the E form of G (as you’re already doing). Playing and saying the scale degrees, then note names.

2) Transpose the form up the neck to Ab and play them all while saying the note names. Then do key of A, then Bb, etc. (and remember, go slow, it’s not a race). If you need to, write out the spellings of the chords in each new key on a sheet of paper and use it until you’ve got the note names memorized.

3) After you’ve done all the keys with the E form, go back down the neck and use the A form of C. You’ll notice a lot if similarities in the fingerings (the fingerings you played on strings 654 will be the same only on 543). Use your knowledge of the intervals and notes to extend up to the 1st string and then down to the 6th string.

4) Then transpose the A form up the neck the same way you did for the E form in step 2, saying the name of every note.

5) Repeat this process for the remaining forms (D form, G form and C form)I think you’ll find that working this out on the instrument in this way is really empowering. You’ll come away from it with a much deeper knowledge of not only the notes all over the fretboard, but also the spellings of chords and the functions of the chord tones (which is really essential when you’re improvising).

Many people look for shortcuts, but the reality is there really are no shortcuts, just distractions from getting the important work done. A solid foundation in the basics is necessary for progress in any other area to really take hold.

Musically Yours,

~ Rick -

I highly recommend the William G. Leavitt books; Modern Method for Guitar Complete 12&3, Melodic Rhythms for Guitar, Sight-Reading Method, etc. While not exactly “jazz” books, they’re an invaluable reference for technique, reading and general musicianship.

The good old Mickey Baker “How to Play Jazz Guitar” has been around for years, but is still an excellent source for learning rhythm section chords and some basic substitution principles.

Another great resource for chords is the Joe Pass “Guitar Chords” book. It’s just kind of a grab-bag of voicings grouped into Major, Minor and Dominant, but they all sound good and can help get you out of a rut.

Mick Goodrick’s “The Advancing Guitarist” is another one with some great ideas.

Mark Levine’s “Jazz Piano Book” and “Jazz Theory Book” answer a ton of questions that most players have.

A couple excellent books that deal more with internal processes are Jonathan Harnum’s “The Practice of Practice” and Kenny Werner’s “Effortless Mastery.” I drawn a lot of inspiration as a teacher from both of them.

I’m short on time right now, but I’ll probably come back when I think of some more.

-

David,

Thanks much for the kind words. Please let me know what you would like to see here. I’m trying to add new material every week!

Musically Yours,

~ Rick -

John,

Thanks for writing. I know this has been highly requested, but the truth is, it’s a copyright issue. Wasn’t such a big deal when there were only a handful of my private students using the site, but as we grow, it could become a huge liability. You may have noticed that some of the more recent tune-based lessons (see “ATTYA” and “Autumnal Eves”) use contrafacts rather than the original melodies. This is because copyrights cover the melody and lyrics, but don’t extend to chord progressions (tons of songs use the same chord progressions, think “Ornithology” aka “How High the Moon,” “Donna Lee” aka “Indiana,” and countless songs based on “I Got Rhythm” or the blues).

I could probably give you the chord voicings I used (without the actual arrangement of the melody) and stay within the law. But as far as the melodies are concerned, I think I’m going to be sticking with writing contrafacts on the tunes. And to be fair, the melodies are in the Real Book (which is now available legally), so this really shouldn’t be a big deal.

Musically Yours,

~ Rick -

Bob,

You can certainly start on almost anything, but you’ll notice that for Dominant 7th Scales, running the chords on 3rd, 5th or 7th definitely retain more of the sound of the change. I think it’s also important to note that the ends of your lines (where you land) are far more important than the beginnings. And of course, the less time you have on a change, the more focused you want your ideas to be. Consider John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps” solo; most of the phrases are just 1235, 1531, or a descending dominant scale with a single chromatic between 1 and b7. When changes move fast, you pretty much just have to nail it. On the other hand, if you’re playing over a chord that hangs out for awhile (as in a modal situation) you have a lot more leeway to stray because you’ll have time to resolve the idea.

~ Rick -

Nick,

When transcribing, do you write out the lick or phrase you’re working on? Writing the idea down will help you to analyze it and break it into manageable chunks. Try to identify what structures (triads, chords, scales, chromatics, enclosures, etc.) are being utilized and their relation to the “key of the moment.”

Another kind of “quick and dirty” method that works real well is to look at how many strings the lick spans and what finger you started on. Does it start on the 1st finger and encompass strings 5-4-3-2? You should then probably be able to start on the same finger and and play it from the same finger on strings 4-3-2-1 or strings 6-5-4-3 (with some adjustments to account for the tuning).

Then look to see if it can be started from a different finger and repeat the above procedure.

Check out Part 2 of this lesson: https://www.jazzguitarlessons.com/building-bebop-lines/

I use the CAGED system to find 5 locations on the neck for the same lick.I’ve also written a couple blog posts on transcribing that you might want to check out:

https://www.jazzguitarlessons.com/learning-from-the-masters/

https://www.jazzguitarlessons.com/some-tips-on-transcibing/Hope this helps.

~ Rick

-

Just wanted to let you know that the lines from the Connecting Dominant 7th Lines on Rhythm Changes Bridge are now transcribed and posted to the lesson at https://www.jazzguitarlessons.com/connecting-dominant-7th-line/

I’ve also posted 2 new videos (with notation) on Building Bebop Lines. I think you’ll find them interesting.

https://www.jazzguitarlessons.com/building-bebop-lines/ -

John,

No problem. I actually love it when people ask me questions like this because it motivates me to write. There are so many topics I could write a blog post about, but having something immediately relevant is very helpful. So anyway, my answer to question did get fleshed out and edited a bit more and I posted it it here: https://www.jazzguitarlessons.com/how-to-create-a-jazz-guitar-chord-solo/. Thanks!

Musically Yours,

~ Rick -

John,

I know what you mean, but “borrowed time” or not, I can tell you from my personal experience that the best way to do this

(and by “best” I mean the way that’s most enjoyable and will help you to really learn to play a tune in a way that feels natural to you and the knowledge will stick) is to spend a lot of time listening to the tune, learning the lyrics and the melody, learning to feel where you want to place the chords belong (rhythmically) and then deciding which chord voicings you like play in those places.That said, this is something that I do with my private and Skype students and maybe I could do a video about this because

it is the way the process works for me (I think that I actually kind of do this in the “Satin Doll” lesson, but

maybe I could have gone more in-depth).In the meantime, here’s a kind of procedure that I use all the time:

1. Pick a tune that you like. It can be one you’ve heard on the radio or on a cd, or if you go to jam sessions or places where you might have a chance to sit it, pick something that they play. Whatever it is, it should be a tune that you can get excited about. A tune that you really want to learn.

2. Go through your record, cd, mp3 collection and find and listen to as many versions of the tune as you can. If it’s a tune with lyrics, at least some of those versions should be with singers. If you feel like your collection is pretty weak for that tune (if you can’t find at least about 5 versions or so) then go online and find some more (I usually use this as an opportunity to use of some of my eMusic credits and wind up with anywhere from 15-30 versions of a tune).

3. Listen, listen, listen! This is the fun part. Enjoy it!

4. Memorize the lyrics. I used to write them down on an index card and keep it in my pocket. As I’d just be going about my business for the next few days (buying groceries, working in the yard, or whatever) the tune was constantly in my head. I’d find myself just singing it to myself. Didn’t really have to try to do anything, this just happens. If I couldn’t remember a lyric, it would bug me and I’d pull out the card and read just the line that I needed, then put it back and continue.

5. Try to play the melody on the guitar by ear. Doesn’t really matter what key at this point. Just wherever it feels comfortable. You’ll probably want to check with some of the recordings you’re listening to though and pay attention to what key(s) most players like to do the song in. Learn the melody in the most common key first, then try it in a few others. If you’re going to do a chord melody, you’ll probably find that it lays much better on the guitar in some keys than others.

6. After you’re familiar with the melody, you’ll want to start thinking about the chords (these two activities sometimes overlap). If your ears are pretty developed, you might just get them straight from the recording. But if you need a little help, you can take a look at a fake book. Most professional musicians I know keep iReal Pro on our smart phones so that we’ve got a quick reference if we have to play a tune we’re not all that familiar with). Just be aware that these things aren’t always accurate and that chord changes can vary slightly from one version of a tune to another, so you have to decide whose changes you want to use. You’ll probably want to write out your own sheet with the changes you prefer.

7. Memorize the changes: Practice reciting them (yes, say the out loud!). When you first try to do this, you’ll probably find it impossible to recite the changes to a whole tune from memory, so break it into bite-size pieces. Memorize from 2 to 4 measures at a time (about 4 chords) and just say them in order until it’s easy and natural (like remembering a phone number). Then do the next few chords. Then put them together. Do this until you can get through saying the changes for the entire tune from memory. As with the lyrics, I’ve always found it useful to write the changes out on a sticky note or file card and keep it in my pocket as a quick reference while I’m doing this. Try not to just read it off the paper though. Glance at it for the information you need and then put it away and get back to the work of memorizing. I actually like to do this when I’m out walking or jogging because it forces me to do it in rhythm (your footsteps become your metronome) and I hear the tune in my head as I’m saying the changes. I should also mention that at this stage of the game, I’m only interested in the most basic family of the chord; Major, Minor, Seventh (and sometimes Diminished).

8. Back at the guitar, play that melody and really pay attention to where you feel the chords belong. Sometimes they’ll be right on a melody note, but often you’ll notice that they fall in between melody notes (like the chord changes in “Autumn Leaves” that fall mostly between the phrases). Use your ears and your knowledge of the melody and chords to choose voicings that you like (I did a lesson video the other week on Chord Melody Voicings that you’ll probably be interested in).

9. Play the tune A LOT! I often spend weeks on a tune, coming back to it day after day. I’ll often make little changes and improvements to my arrangement as I go. The way I play the tune evolves over time until I arrive at something I’m happy with.The point of all this is that playing jazz music is more about a journey than it is about a destination. I’ve been doing this stuff for many years, and what I just outlined above is still the way I approach learning a new tune. I do it because for one thing it’s just enjoyable in and of itself (I can lost in a tune for hours, days or weeks) but also because I know it works so I just trust the process.

Hope this helps!

Musically Yours,

~ Rick StoneP.S. This answer got to be so long that I think it’s probably going to show up as a post on the blog.

-

I’d start with the obvious and just transpose each fingering up and down the neck chromatically. I’d also say the key and/or the names of the chords out loud for each key so that you form a really strong impression of the exact notes and location on the neck. Try to break the phrase down and analyze the chord/scale tones, chromatics, triads and other structures too.

-

Nick,

Yeah, writing them down at first will definitely help. After you’ve done it for awhile and are more familiar with a lot of the commonly used structures, it becomes easier to just remember, but keeping a notebook of licks and phrases as your learning is useful in that it becomes a log of what you were practicing at any given time. BTW, I’d advise that for every lick you put in your notebook, you write the date you learned it, the source of the lick, and the chords that it goes with. I wish I’d done this all along because years later, I’ve found tons of things that I wrote and after awhile, you’ll have so much of this stuff that it’s difficult to remember where they came from (and wonder; was it a tune that I was writing? a lick I was working on? something I transcribed? or what?).

It doesn’t take me terribly long to work out several good fingerings and play a lick in any key (usually just a few minutes) but I remember spending at least an hour (or more) on each lick or phrase when I first started doing this many years ago. As you get better at it, you’ll find that you learn and retain much faster.

I think learning one new lick a day is a great thing to add to your practice routine. Remember, we’re not talking about a ton of music here, just 2, 4 or 8 measures dealing with a particular chord change (or changes). Keep it simple at first and you’ll learn faster. Then expand as you feel able to.

Musically Yours,

~ Rick-

This reply was modified 9 years, 7 months ago by

Rick Stone.

-

This reply was modified 9 years, 7 months ago by

-

John,

Thanks for the kind words. Glad that you’re loving the lessons. As you can see, I’m trying to add new material regularly and value everybody’s input. You’ll also see that I’m much more of the “teach a man to fish” than the “give a man a fish” school of thinking. So what I’d really love to see you come away from these lessons with, is the ability to create your own licks and phrases.

Musically Yours,

~ Rick Stone -

AuthorPosts